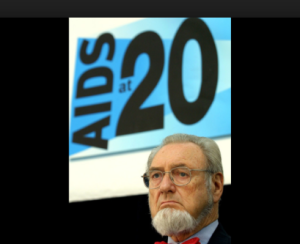

C. Everett Koop, a Hero During the AIDS Crisis

When Ronald Reagan was elected to the presidency in 1980, names of faithful members of the conservative right were submitted to his Administration for possible appointment. Virtually all the suggestions were ignored—except the one to appoint C. Everett Koop as Surgeon General. As it turned out, Koop became the Surgeon General no one expected.

The Senate battle over Koop's appointment as Surgeon General

Koop had been the co-founder in 1975 of the Christian Action Council, the

leading evangelical antiabortion action group in the United States. As such, he’d been approached even before the election by Reagan’s team. Koop, steeped in conservative thinking, writing, and speaking, was seen by the Religious Right as a strong leader in the Christian prolife movement and an ideal candidate for the office of Surgeon General. Democrats, meanwhile, were passionately opposed to Koop’s nomination. Medical groups, public health groups, and women’s right-to-choose groups pounded Congress over a period of eight months, objecting to Koop’s appointment.

Even as his embattled confirmation hearings ensued, Koop was aware of twenty-six recorded deaths in a single month from Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. Because he had only seen two cases of the disease in his forty years as a surgeon, he knew the deaths indicated the makings of an epidemic.

When his appointment was finally confirmed, Koop was convinced that he had a mandate to educate the American public about AIDS, for which there was still no cure in sight. But for the first four years of his term, not only was Koop prevented from speaking directly to Reagan about the epidemic but he was also banned by his boss, Robert Schweiker, the Secretary of Health, from addressing the public about it.

New Secretary of Health Heckler was completely unaware of AIDS before her 1983 appointment

When Margaret Heckler replaced Schweiker in 1983, she immediately asked a staff assistant about department priorities. Later, she recalled the conversation:

I was quite surprised to learn from a conversation with David Winston, who had been a staff member of the Senate Health Committee under then-Sen. [Robert] Schweiker, and who had served with Gov. Reagan at the Health Department in California . . . I asked his recommendations on the priorities I might set, and he said, “Oh, well, you must begin with AIDS.” I said, “AIDS?” I had never heard of AIDS. “What is AIDS?” He said, “This is a disease that is killing young people, and the hospital wards in San Francisco are crowded—in fact, bulging.” I said, “Well, I have never been briefed on this; I have never heard of it.” I had just gone through the whole confirmation process, and it had never been mentioned.

Immediately, Heckler attempted to approach Reagan for AIDS funding allocations, but never succeeded in speaking to him about it—though not for lack of trying. Reagan’s priorities were economic stability and cutting the budget.

Koop tries unsuccessfully to meet with Reagan

Koop later wrote, “At least a dozen times I pleaded with my critics in the White House to let me have a meeting with President Reagan.” Instead, Koop says of the issue, too many people “placed conservative ideology far above saving human lives.”

Similarly, Koop later stated, “Our first public health priority, to stop the further  transmission of the AIDS virus, became needlessly mired in the homosexual politics of the early 1980s. We lost a great deal of precious time because of this, and I suspect we lost some lives as well.”

transmission of the AIDS virus, became needlessly mired in the homosexual politics of the early 1980s. We lost a great deal of precious time because of this, and I suspect we lost some lives as well.”

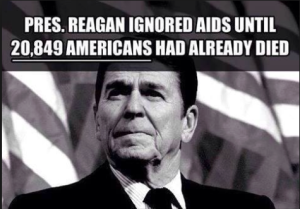

The AIDS crisis in America continued to grow at alarming rates while Reagan remained silent on the issue. Researchers, health care professionals, and doctors at the Centers for Disease Control and elsewhere were screaming for funding, yet Reagan remained silent.

On July 25, 1985, a hospital in Paris announced that the famous actor Rock Hudson, a close friend of Nancy and Ronald Reagan, had been diagnosed with AIDS; this news was reported widely, but still, Reagan remained silent.

Finally, on February 5, 1986, five years into the outbreak, on a surprise visit to the Department of Health and Human Services, unexpectedly Reagan said, “One of our biggest public health priorities is going to be to find a cure for AIDS.” Then he instructed Koop to prepare a report on the disease.

In drafts of the report, Koop advised condom usage to prevent the spread of AIDS. Knowing that Reagan’s inner circle and domestic-policy advisors would delete any reference to condoms and sex education, Koop strategically guarded review copies of the drafts. At meetings, he handed out numbered copies and collected all of them at the conclusion.

Though Dr. Koop was pushed by White House aides to ensure that the final report would be morally judgmental of the gay community, he would not succumb to the pressures. His evasive strategy with the White House worked.

Koop releases HIV/AIDS Report nationwide

On October 22, 1986, “The Surgeon General’s Report on AIDS” was released. It was praised as “accurate, nonjudgmental, and comprehensive information on the HIV/AIDS epidemic, educating Americans in plain language about how the virus could and could not be spread and how individuals could protect themselves.

On October 22, 1986, “The Surgeon General’s Report on AIDS” was released. It was praised as “accurate, nonjudgmental, and comprehensive information on the HIV/AIDS epidemic, educating Americans in plain language about how the virus could and could not be spread and how individuals could protect themselves.

The report said that the best protection against AIDS was abstinence and monogamy, but that for those who practiced neither, condoms were a necessary precaution.” Koop’s prior detractors were stunned that the report was not the moral judgment on the gay community that they had expected.

Twenty million copies of the Surgeon General’s initial report were distributed to local governments, schools, and doctors. In the introduction to the report, Koop pointed criticism directly at the Religious Right’s attempt to blame AIDS on the gay community, writing:

At the beginning of the AIDS epidemic, many Americans had little sympathy for people with AIDS. The feeling was that somehow people from certain groups “deserved” their illness. Let us put those feelings behind us. We are fighting a disease, not a people. Those who are already afflicted are sick people and need our care, as do all sick patients. The country must face this epidemic as a unified society. We must prevent the spread of AIDS while at the same time preserving our humanity and intimacy.

The Religious Right attacks the Koop report

Along with condom usage, the report advocated sex education and AIDS

prevention education for students in the third grade and above. Immediately, Phyllis Schlafly of the Eagle Forum criticized Koop. She said it looked like the report “was edited by the Gay Task Force.” She also accused Koop of advocating for third graders to be taught how to engage in “safe sodomy.” Koop responded, “I’m not the Surgeon General to make Phyllis Schlafly happy. I’m Surgeon General to save lives.”

The Conservative Digest, founded by Paul Weyrich associate Richard Viguerie, echoed Schlafly’s exaggerated concerns, stating that Koop was “proposing instruction in buggery for schoolchildren as young as a third grade on the spurious grounds that the problem is one of ignorance and not morality.” The National Review, founded by conservative William F. Buckley in 1955, wrote that Koop was “criminally negligent” in advocating the use of condoms.

Koop was a disappointment to the conservative right

Dr. Koop was a disappointment to those who had put forth his name as a nominee and had advocated for his position as Surgeon General. His track record and strong performance as an abortion opponent had seemed to make him the ideal conservative candidate. Before his appointment, Koop had made no secret of his conservative religious leanings; in fact, he had spoken dismissively about “women’s lib” and “gay pride,” saying that both ideologies were anti-family. He was a conservative Christian raised in the Dutch Reformed Church who held staunch Calvinist views that the purpose of government was to uphold morality.

But during his confirmation hearings, Koop had assured the concerned Senate panel that he would not use his office to promote religious ideology, and he did not. In the struggle between public health and “morality,” he saw it as his duty to protect public health. In the conflict between medical evidence and religious beliefs, Koop formed his opinions and took his directives based on medical evidence. He said, “My position on AIDS was dictated by scientific integrity and Christian compassion.”

Koop was a man of compassion

Once he had encountered people living with AIDS, Dr. Koop made an intentional decision to distance himself from the non-compassionate ideology of those who had promoted him to the office. In the year following the Koop report, condom sales increased by 20%, thus decreasing the transmission of HIV and saving lives. Rather than positioning the spread of AIDS as something that could be stopped by preaching against it or outlawing “immoral” behavior, Koop’s report had succeeded, at least for the most part, in dispelling the misunderstandings and myths that only gay men and drug users contracted HIV.

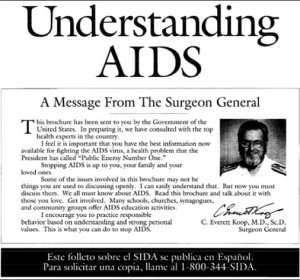

After informing public and medical officials of best practices with the initial October 1986 report, Dr. Koop launched the first nationwide HIV/AIDS education program and orchestrated the largest-ever public health campaign by sending a version of his report, called “Understanding AIDS,” to all 107 million American households in May 1987. The pamphlet informed the public about HIV/AIDS transmission methods, clearly stating that HIV/AIDS could not be transferred through casual contact, but only through sexual contact, needle sharing, or contact with contaminated blood.

After informing public and medical officials of best practices with the initial October 1986 report, Dr. Koop launched the first nationwide HIV/AIDS education program and orchestrated the largest-ever public health campaign by sending a version of his report, called “Understanding AIDS,” to all 107 million American households in May 1987. The pamphlet informed the public about HIV/AIDS transmission methods, clearly stating that HIV/AIDS could not be transferred through casual contact, but only through sexual contact, needle sharing, or contact with contaminated blood.

President Reagan finally speaks of AIDS publicly

In the same month, on May 31, 1987, the President of the United States finally publicly spoke the word “AIDS” at the Third International Conference on AIDS in Washington, D.C. By then, over 36,000 Americans had been diagnosed with AIDS, and almost 21,000 had already died.

When Dr. Koop left office in 1989, the New York Times editorial board, which had previously weighed in against his appointment, praised him: “Throughout, he has put medical integrity above personal value judgment and has been, indeed, the nation’s First Doctor.” Koop put medicine and science ahead of politics, holding his strong personal beliefs about homosexuality in tension with his duties as Surgeon General.

*************************

This information is found and footnoted in Walking the Bridgeless Canyon by Kathy Baldock, Chapter 8.

This information is found and footnoted in Walking the Bridgeless Canyon by Kathy Baldock, Chapter 8.

READ the other five parts of this special series on HIV/AIDS:

What Caused the Onset of HIV/AIDS? Colonialism

AIDS Migrates From Africa to Haiti and the U.S.

How I Responded to the AIDS Crisis in the 1980s

The Face of AIDS Becomes a Child -- Ryan White

Early Christian Responses to Epidemics Completely Unlike the 1980s Response